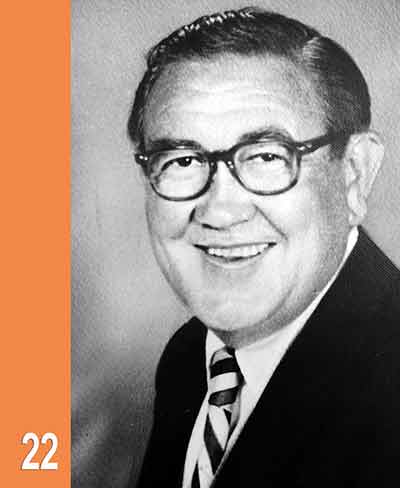

Tom Little

Induction Year:¬Ý1979

Lived:¬Ý1898-1972

Paper:

The Tennessean, Nashville

In more than a half century with the Tennessean, Tom Little filled an astonishingly varied assortment of roles. For the record, he began in 1918 while still in school. He worked as a police reporter, city editor and at least a dozen other assignments. But it was as the newspaper's editorial cartoonist that he won a loyal following, national attention and major prizes. His tough, stark, uncompromising drawings were so popular it was often said more of his cartoons were reprinted in other newspapers and periodicals than any other cartoonist of his time.

Yet it was for a touching drawing of a child on crutches watching other children playing football that he won the 1957 Pulitzer Prize. Even that cartoon was from the mainstream of the Little tradition. Entitled "Wonder Why My Parents Didn't Give Me Salk Shots?," Little said it was aimed at parental apathy surrounding the new cure for polio.Proud of his Pulitzer and the Headliner Award he had received earlier, Little was more at home drawing biting caricatures which gave presidents, governors, mayors and even the Republican party--one of his favorite subjects--indigestion.

"You rarely accomplish something good by praising something in a cartoon," he explained. "To promote something good you have to point out something bad on the other side. Good cartoons are not funny. They are serious business. People don't laugh at them, they get mad at them."

And for more than three decades, seven days a week, his cartoons angered, embarrassed and touched the raw nerves of his subjects as well as his readers.

Little's first national exposure came when he drew his first syndicated feature, "Abner Simp," in the early 1920s. His second, the one most widely remembered, was "Sunflower Street," a panel he drew for King Features Syndicate for more than 15 years while producing his daily editorial cartoon. Later he drew the cartoon illustrations for the New York Times magazine. Despite his successes and national fame, "Sunflower Street" became one of his most bitter disappointments. It was a panel about blacks, and his decision to quit drawing it in 1950 came when editors were becoming leery of using it because of fear it might be construed as "looking down" on black people.

His disappointment was understandable for Little had, during his more than 30 years of cartooning, championed, rather than tried to undermine, the rights of the minority races ad creeds in the South. Luckily for Little, the same pressures that brought an end to "Sunflower Street" did not spill over into his political cartoons. For him it was always open season on dishonesty, laziness, stupidity and corruption in high places. He continued to jab and poke and slash at politicians with unrestrained glee.

Little, the Williamson County boy who originally started out to be a writer and wound up a nationally famous cartoonist, stayed with the Tennessean until 1970, when his health began to fail. He retired two months before he suffered a massive stroke in 1970. He died two years later.